This is a topic near and dear to my heart. We all “strive for balance” in our lives – trying to juggle home, work, and play. Sometimes we tip too far to one side or the other. Sometimes that “balance” is upset and we have to make a course correction!

When we’re talking about our physical bodies, balance is just as important – and just as complex! Most of us don’t realize we are starting to “lose our balance” until family members start commenting on our walking and posture (“Why don’t you stand up straight anymore?” “Stop shuffling!”) or we have an actual fall. Currently 1 in 4 adults age 65 and older report falling every year.

It can be frustrating to realize you’ve lost confidence in daily activities that used to seem so easy: walking on cobblestones or the beach, climbing a ladder, carrying the laundry up and down the stairs without holding the rail.

The good news is, balance can be worked on and improved at any age. In today’s post, we are going to talk about:

- Myths vs Fact – Why DOES our balance decline?

- The three main components of our overall balance

- Other factors that play into finding–and keeping–our balance

Myths – The Stories We Tell Ourselves

Let’s first address some myths about balance. Oftentimes we hear these statements from friends, family – even from some healthcare professionals!

Myth #1: Losing your balance is “inevitable” as you age.

While it is true that, physiologically speaking, we have muscle, joint, tendon, and ligament changes with advancing age (think: longer recovery time for those aches and pains!) and older adults are more likely to experience a decline in balance and confidence in functional activities, falling itself is NOT part of the normal aging process.

Myth #2: If I avoid activities that make me feel unsteady, I’ll never fall.

As a practicing Physical Therapist working with folks with a wide range of abilities, I always tell my clients and patients that safety at home and out in the community is PARAMOUNT. That being said, our balance declines most rapidly when we start self-limiting our daily challenges to our balance – oftentimes without even realizing it!

This is the “use it or lose it” conundrum–if you avoid walking on grass and always opt for the smooth pavement, you are going to “lose” the ability to walk on grass or other uneven surfaces.

If you always use your hands to push up to standing from your favorite chair, you’re going to lose the strength and balance to get up from a seat without chair arms.

If you always go in the house by the side door because it bypasses the steep stairs to get in the front or garage door, you are going to lose the confidence to take those larger steps for things like street curbs and safely getting in and out of a tub shower.

This myth of avoiding feeling unsteady in order to avoid falling is a tricky one – it’s true in the short term (we as PT’s never want our patients or friends and family members to fall at home), but it is not a great long term solution.

In fact, fear of falling itself can provoke future falls. If you are noticing you are limiting your usual activities in order to avoid a fall or “feel more steady,” talk to your doctor and/or Physical Therapist about coming in for a balance “tune-up.”

Myth #3: Once my balance is gone, I’m too old to get it back

I love busting this myth – you can make improvements in your balance at any age! In fact, programs for older adults to practice and improve balance have been shown to improve postural control, balance confidence, cognitive function including memory and spatial awareness, and quality of life measures including walking speed and elevated mood.

Part of the reason for this wonderful ability of our brains and bodies to improve our balance with practice is that we can attack the issue of balance from several avenues, including our vision, our vestibular system, and our sensation/proprioception. If these vocab words sound daunting, never fear! We are going to dive into each of these systems – and how they contribute to our balance – next.

Three Main Components of Our Balance

We’re now going to discuss the three main components that factor into our experience and maintenance of our balance: our vision and eye movements, our vestibular system or “inner ear,” and our sensation in our feet and our proprioception or “position sense” in our joints.

Vision

Most of us rely on our vision quite a bit for our balance. Think about what happens when you have to walk to the bathroom at night in the dark. Or imagine trying to complete Tree Pose in yoga – but with your eyes closed!

Our eyes are constantly giving our brain and therefore our body information about our environment, what is safe or not safe, what obstacles are in our path that we need to step around, over, or avoid completely, and what helpers might be at hand to aid us in keeping our balance (ie that handrail you automatically reach for in an unfamiliar stairwell).

Our brain processes this information immediately and sends instructions to your body to do what is “most safe” or at the very least “the most predictable,” ie “If I place my hand on this door jam, I know my foot will clear that same old crack in the floor.”

Conversely, your eyes will alert your brain and body to an unfamiliar situation, like a set of steps at your daughter-in-law’s house that is steeper than the one you have at home. With that visual information, your brain will tell your body to reach for that railing, or even go up only one foot at a time.

Thank goodness our eyes can do this – our body automatically kicks in to step over a gopher hole or deep crack in the sidewalk. Scanning or looking around your environment both at home and out in the community can be a very helpful way to keep yourself from tripping over a stray rug or toy left out by the grandkids.

The Vestibular System

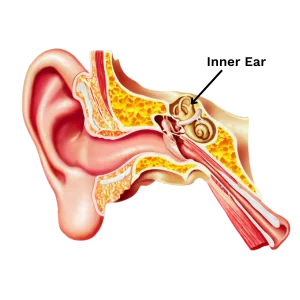

Your vestibular system or “inner ear” is actually also linked to your vision and eye movements, but we are going to separate it out a bit here.

Your inner ear lays beyond the eardrum and is made up of three canals filled with fluid and lined with small hairs. When the canal fluid shifts with changes in head position, the liquid deflects the hairs, which then sends sensory information to your brain about where your head is oriented/located in comparison to your environment and your body.

Think about stepping on a floating dock or turning your head to have a conversation while walking with a friend – your vestibular system allows your body to make adjustments in muscle activation, foot placement, etc to maintain your balance with these changes in head position.

Again, thank goodness we don’t fall over every time we turn our head to watch for oncoming traffic before navigating a crosswalk.

Our Sensation/Proprioception

And finally, the sensation in our feet and the proprioception or “position sense” in our joints! Our feet contain thousands of nerve endings of several different types that provide our brain with sensory information to tell us about the condition of the surface we are stepping on – is it smooth? Bumpy? Is it too hot or cold? Is it slick and icy?

Our brain makes immediate adjustments to our muscles to keep us safe – leaping our bare feet off a hot stretch of summer pavement or quickly decreasing our step length and putting our arms out to the side to avoid slipping in an icy parking lot. (These nerve endings are often stifled when we end up wearing stiff, thick-soled shoes 24-7, but that is a topic for another article!)

When we talk about proprioception, we are referencing a special type of sensory information, namely the nerves in our joints (and other places) that tell our brain where our body and limbs are located in space.

This can be as simple as closing your eyes, lifting your arm, and being able to tell which direction your hand is pointing.

But it can also be more subtle – proprioception is what allows you to navigate up and down steps of varying heights without stubbing your toe every time. Your proprioception tells your brain, and your brain tells your body, whether to automatically make a larger or smaller movement to land square on the step.

It also allows you to reach behind your shoulder without looking for that driver’s side seatbelt.

These Systems Work Together

These systems do work together to maintain our balance, but we also use specific exercises to target each of the different systems. Do you rely too much upon your visual system (like most of us) to balance? Your PT will help you SAFELY practice balancing with your eyes closed – thereby beefing up your vestibular and sensory systems. Throw in some head turns with that single leg balance in Tree Pose and suddenly you are stimulating your inner ear. The options for challenging your balance are endless.

Final Factors To Consider

These systems work in tandem with each other – and with the rest of your neuromusculoskeletal system. A licensed Physical Therapist can work with you on a whole body approach to improve your balance and help you gain confidence in navigating your home and community.

For example, are your feet and ankles too stiff and/or weak to make small, quick adjustments to changes in terrain? Do the muscles in your hips fatigue when you try to step over a tall guard rail so you tip to the side? Has your neck “always been tight” so that your lack of head movement fails to regularly stimulate your vestibular system? Do you just not know “how much is too much?” when trying to safely and effectively improve your balance?

If any of these questions ring a bell – or prompt you to more closely examine your own confidence with balance – contact your favorite PT today.

Contributed by Caitlin Steeves, PT, DPT